How fast a balloon floats?

11-Apr-2021

Balloon that floats…

My daughter recently got two helium balloon that floats, it was gifted. While she played with it, at some point, both balloons touched the ceiling at almost the same time. The balloons are attached to a light string so we can pull the balloon down again.

I don’t know exactly what gas they used to fill the balloon, but I’m guessing it’s Helium. Helium is a light noble gas, lighter than air. But, what does it mean by saying lighter than air? It is more accurate to say that Helium gas were less dense than air density in room temperature.

The concept of air density, is similar with fluid density or liquid density. You divide the mass with the volume that the mass occupies. However, gas can be compressed. So, normally if you compare air density, you declare the the pressure and temperature between them.

To understand how balloon floats, we will talk a little bit about the physics behind it. Simply speaking, in the surface of the earth, any object will be affected by gravity. This includes air. Air contains groups of molecules. If they were located in the same gravitational potential, they will contain the same potential energy. These group of air will need to have a matching internal energy that is “bound” by the gravity. If their internal energy is higher, they will naturally floats higher, where the potential energy is higher than the surface (less gravity). By “migrating” into area which have higher potential energy, they converted their internal energy into potential energy.

In the case of air, since a volume of air is compressible. Sometimes we associate internal energy of volumes of air (macroscopic quanity) with it’s pressure. This is why we have the equation where the right hand side basically contains information about the energy (albeit with some modification, depending on the gas). Back with the balloon, we can say, denser/heavier air will try to settle down because it was affected by gravity. This will cause the denser air below to push (by the pressure difference) lesser dense air to float, until it settles in their preferred height.

The somewhat invisible force that moved the balloon up is most commonly called Buoyant force. People also called it Archimedes Principle in honoring Archimedes, the greek philosopher that rediscover this principles. The buoyant force is defined like this:

Where: is the density of the surrounding fluid, is the displaced volumes and is the average gravity in that position.

Naturally, we usually think that air density is different by height from the surface of the earth, due to gravitational potential I described earlier. To simplify things, we limit ourselves to only observe floating balloon in uniform air density, such as inside a room. We are talking about my daughter’s balloon here, not atmospheric balloon. :p

Slow free-floating balloon in a room

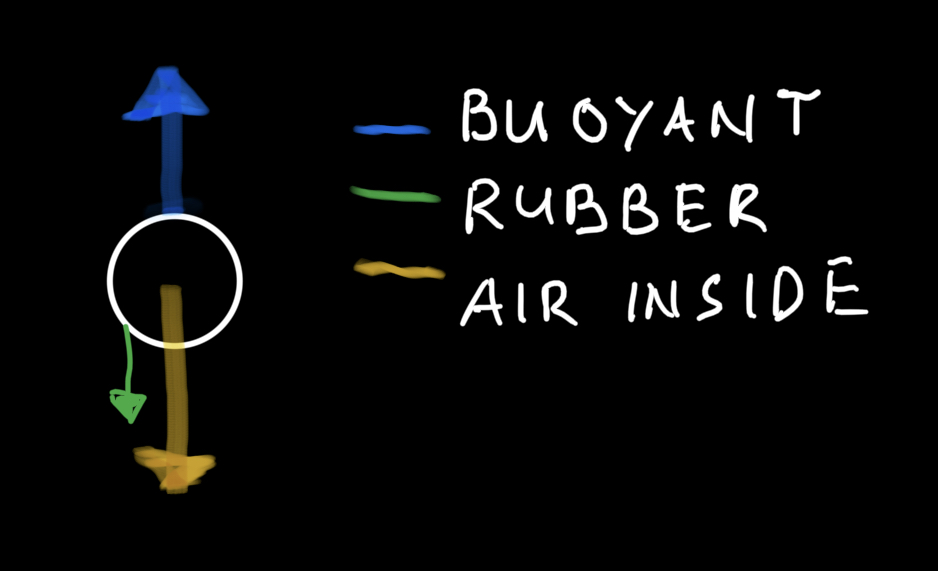

Let’s observe a simple case of free-floating balloon in a room. We identify there exists macroscopic force, i.e: buoyant force and gravitational force . We are going to ignore drag force by saying that the balloon is slow moving (making the drag force negligible). Since usually the weight of the rubber balloon and the weight of the air inside is not significantly different, we can’t ignore the rubber weight, so we include it in the equation as , meanwhile the weight of the air inside the balloon is called . Check out my ugly force diagram for clarity.

Using Newton’s Second Law:

The equation above uses these implicit assumptions:

- Balloon’s shape was not going to be deformed and stable

- No turbulent

- Balloon strictly only floats in y direction

- Air pressure and density inside the room is uniform and constant

- Drag force is ignored because the balloon travels slowly and relatively negligible compared with the other force

If we observe the final equation, it turns out that the acceleration is constant! We predict that the velocity will increase to infinity, but of course that is incorrect because in the real situation, the air density will decrease in high-altitude. Moreover, when the drag force becomes significant, the velocity will be limited into a terminal velocity. However, in our case with short distance inside a room (from the floor to the ceiling) this will suffice.

We can make some fun conclusions from this equation alone. In the second term, we are going to see how big the value is. Let’s try with Helium, at STP (standard temperature & pressure) it has . I can’t measure the flat balloon‘s mass, because it’s too small. But to be safe, let’s say it is 1.5 g (between 1 and 2), which is equal to . A typical balloon can have the shape of the sphere (again, simple assumptions) with radius of 10 cm. So it would be around in volume. In summary, the term will be around 2.3 ratio. Combined with the third term, the first term will be subtracted by 3.3.

Now let’s estimate the first term. Standard air density at STP is around . The first term will be around 7.08 in value. So the final upward acceleration is about 3.62 times the gravitational acceleration. This is quite surprising to me because the rate that the balloon floats is actually much faster than the rate of people falling by more than 3 times.

You would think that this is very fishy. If you drop a ball and let balloon afloats, even if the direction is the opposite, you can clearly tell that obviously the object falling is much faster than balloon floats. So, our estimate is only valid for a very-very short distance but not yet accurate for room height.

There is also another possibility. It could be that a typical Helium party balloon is not purely composed by Helium. It might be a mix of Helium and regular air. Who knows…

Anyway, it’s also interesting to note, the above formula for also valid for any mix of air inside a balloon. That means, if you put regular air inside the balloon, the acceleration will be negative and the balloon falls down. If you assume that the density inside and outside the balloon is the same, first term and third term will cancel out. Then the second term is decidingly negative.

However, if you put normal air inside a balloon, it tends to be denser because the rubber will slightly compress the air inside the balloon causing more air is trapped inside the balloon with the same pressure. Thus even the balloon’ s content will be heavier than the surrounding air and falls down.

To compare it, imagine if you fill the balloon with water completely, and then put inside a pool. The balloon will floats below the surface, but doesn’t touch the ground. This is because water’s pressure is significantly stronger and water is less compressible than air, so you can’t pack more water inside a balloon denser than the surrounding water.

Balloon that floats with attached strings…

The previous case seems to be very specific and uninteresting.

My daughter’s balloon, is a little bit special. It has strings/threads attached in it. I observed this balloon day by day. At the first day, we let it touch the ceiling. Then at some point it actually stays midair with part of the strings resting in the floor, even if it was not anchored. Kind of like standing balloon.

Of course, I suspect that the air inside the balloon has partly escaped. But I was more interested in understanding why it floats without anchored. I suspect because the strings can behave as a variable mass.

Since now the balloon is definitely not a pure Helium. We can’t estimate it with numbers easily. But we can predict and models it’s behaviour or dynamics, then kind of match it with the equation.

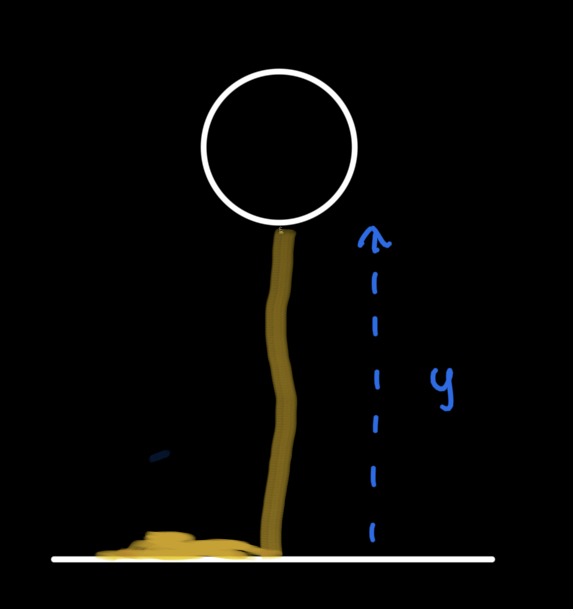

We are going to use the same set of assumptions as before. But now, we add another weight force with regards to the string. I call it ”variable mass” because the amount of weight force it caused is dependent on how long the strings is currently stretched. If we use starting position in the floor, the whole strings are rested in the floor. It’s weights are canceled by the normal force. When it began to float, part of the strings with length (equal to the height of the balloon), will contribute to the balloon’s mass. Check out my ugly diagram again for clarity.

Basically, one extra thing to worry about is the weight of the threads. Since only hanging threads contribute to the weight, and it was based on the height, we define the length density of strings to be . The weight of the strings becomes .

Same Newton’s equation, we now amend it to become:

As we can see now, the acceleration is not constant anymore, but it depends on the height of the balloon from the ground, . This will make the equation above to be a differential equation. To make things compact, let’s rewrite .

It’s a second order linear differential equation. I’m not going to provide the details, but there are ways to solve this equation. For now, let us observe that the equation is really similar with standard Hooke’s Law equation that involves spring oscillations:

Which have solutions in the form:

With same reasoning, we can rearrange original equation to have the same form with the following substitutions:

With the final solutions becomes:

It’s quite surprising to me that the solution, function actually shows that the balloon is oscillating. If given enough strings length, the balloon will have maximum height of and then descends to 0 again. To see how realistic this is, we are going to estimate the values.

The frequency of the oscillations:

If you observe, we can eliminate from . This means, understanding the oscillation does not really depends on the value of . If we make an experiment, it is much easier to predict the experiment outcome from the frequency and amplitude of the experiment.

It turns out that we have bounded values. If no oscillations happens, it means . Because then there is no frequency or it becomes an imaginary value.

Obviously enough, if it doesn’t have enough volumes, it can’t float. But with controlled balloon volume, and known value of the un-inflated balloon, we can estimate the range of the air density inside the balloon, if it does oscillates.

One interesting result from this prediction, is that the criteria is not related with amplitude and gravity at all.

We can then try to validate an experiment. If for example, the balloon oscillates with and , then we can guess that the air density inside the balloon to be close to 0.76 from this formula:

We can also guess that making an oscillations with amplitude 1 meter and frequency 1 Hz is not possible or difficult because then the air density has to be less than Helium.

As you can see above, it may be possible to devise simple experiments for High School level students to measure frequency and amplitude of attached Helium balloon. The string density can be controlled to be attached with pin of weights. This can be an alternative of simple pendulum experiment. In the case of simple pendulum, we usually calculate acceleration of gravity from the frequency of the oscillations. In this case, we can calculate balloon density by measuring the frequency + amplitude, or frequency + linear mass density of the strings.

I’m not a physics teacher. But it would be very interesting for me to see other try to do this kind of experiments.

The last point that I want to show is that this particular equations degenerate or reduces into our special case above if we don’t attach strings to the balloon.

If we treat then the acceleration simply becomes constant again. Although we have to do a little bit of calculus.

Observe that is just a constant, totally unrelated with because it can be eliminated. So, the maximum acceleration is actually the constant acceleration from before, which is:

The acceleration is just because if it doesn’t oscillate, the part becomes 1 (because the frequency is 0).

We can’t do the same trick directly with and function because it will become an undefined form because of the value. But I believe it will reduce to the basic linear velocity increment form if we take the limit.

Floating balloons, attached with strings, with drag force

We are going to up the difficulty a bit. Let’s suppose that we don’t ignore the drag force. How far the model be with the previous model above? Does the previous model sufficiently accurate?

Since usually involving drag force made the whole equation complicated, we are going to take step by step approach. One thing that we can guess from the energy equation, the drag force is a non-conservative force, and dissipative. So it will reduce total energy of the system. If the system without this force is oscillating, then if we include it, it will eventually stop oscillating because it don’t have any energy. But it should still have some characteristic of oscillation, regardless.

Luckily for us, the direction of drag force is predictable. It is always negating the current direction of the velocity. So we can keep the equation in just one axis with Newton’s Law.

There are many definition of drag force. But it will be dependent on the velocity , the surface area of contact , the surrounding air density (in average) , and then a shape coefficient . Historically, for a given shape, people do experiment to determine the drag coefficient and the final form of the formula. I don’t have time for that, so we will going to assume the standard definition of power series:

We reduce all those coefficient/factors into just one coefficient called , which should be determined when the experiment is running.

Usually, drag force only have significant power up to the second power. The definition becomes . However, I have to say, it will be difficult to solve for me. So, we are going to approximate it into the linear order, . If the speed is slow enough, we can define a range of speed that this assumptions will be valid (to some degree). If you want some justification, think like this, between 0.9 and 1, the value of and is not so different. So, our assumptions can only work in those range if . If the coefficient is different, that makes our range becomes different as well.

We now write down the updated Newton’s Second Law, by also incorporating the drag force and constants that we defined in the previous answer.

The above equation is still a second order linear differential equation. It has a standard way to solve it. So we have an easy analytical solutions from that equation. I’m going to skip the derivation to focus more on the final solutions. I will introduce another set of new constant so that we have a more compact form.

By looking at the final solution of we have a more understanding of the kinematics of the balloon.

Just like before, the height is oscillating. However, instead of fixed amplitude , it now becomes . That means the maximum amplitude will diminish over time. Over time, the balloon will stays at height from the ground.

The ballon still oscillates. Although, instead of using the angular speed , it now oscillate with slightly less frequency, . It needs more time to complete a period.

Both the original amplitude and original frequency/angular speed , gets reduced by the factor . Since this is analoguous to a dampening vibration, we’ll just call this new constant the dampening constant. The dampening constant is affected by the drag factor , balloon air density , and it’s volume .

Doing experiment for this kind of situation is a little bit more difficult, but probably more realistic. You can let the balloon float from the ground and then let it oscillates. It will settle down eventually (you can count it’s frequency/period) to a certain height, in which the height must be . From the frequency, you will have . This time, I would prefer to measure directly (using weight scale) the linear density of the strings , so that I can have the value of and then calculate the drag coefficient .

It’s quite interesting that even though the motion equation changes to be more detail and accurate with the inclusion of drag force. The previous constant we defined still usable.

becomes the maximum amplitude possible:

can be measured directly from the experiment by letting the balloon settle down, then measure the height from the ground. can be measured directly, by putting the lump of the strings into a weight scale, then divide by it’s total length. From this constant, we retrieve the air density inside the balloon .

From and we can retrieve . Previously we can measure this, but if we take into account the drag force, then the frequency we measure is actually (Big O) not (little O). From the previous definition of , we retrieve the value.

From the measured frequency (with drag force assumed). We now are able to calculate the dampening factor.

From the dampening factor, we could retrieve the drag coefficient,

As you can see, we can design a fun but simple experiments from this balloon.

Last thing for the curious mind. The solution for , , as function of , all can be degenerated into our previous solution if we treat (ignoring drag force) and causing . Try that for yourself.

Extra Challenge: Solve for quadratic drag force

As I’ve said before, I couldn’t solve the equation if we use . It’s just currently beyond my knowledge. However we can still try to find some insights.

Like before, we hoped that the final solution will degenerate to the solution we got from linear drag force, if the velocity is slow enough.

Additionally, we also hoped that the previous constant we defined does not change and can be reused to construct the new constants.

The main problem is, however, the motion equation is not a linear ODE (Ordinary differential equation).

When the balloon travels upwards, it’s drag force pointing downwards, so during this phase, the equation is:

After it reaches the peak, the balloon should go downwards, so drag force is pointing upwards. During this phase, the equation is:

Honestly, I’ve no idea on how to solve this directly. Usually we convert the equation of motion into an energy equation and then integrate wrt to from there. But, if you try that, you have 3 different function , , and . So, you can’t separate the variable.

What I’m doing instead of integrating, is actually to take derivative once more, on both sides. We are going to do that for upward motion only, for reasons I will state later.

(Also, let’s use the constant , analogous to but for the quadratic drag force)

It now becomes linear in power, but third order, oops.

I will put in a separate article on the way I’m trying to solve it. This article is getting long, so I will just put the solution that I got here. For me, it is quite surprising,

Due to the logarithmic function and absolute values, the mapping goes backwards, a certain acceleration values will entirely define the height of the balloon. Since initial position is , then initial acceleration is as expected. However, due to the function, the balloon will floats and eventually stop because the acceleration can‘t have negative values that will divide the logarithm input to zero.

Interestingly, if we invert the function, we have acceleration as a function of height.

The function is horizontally asymptotic. It’s very quick to reach the limit too, depending on . The negative acceleration limit would be:

Whatever happens during upward motion, the acceleration can’t be any lower than that (pointing downwards when the drag force is significant).

Meanwhile, it’s possible that the balloon will oscillate, just like in the previous case. It will oscillate when the velocity becomes zero . In which, it will try to go downwards. However, the key insight was that this downward acceleration can’t be less than , and the function says it’s asymptotically horizontal approaching this limit.

Remember that I said whatever the solution is, it should degenerate to the previous condition if drag force is negligible. When the drag force is zero. It should match the equation where we don’t have drag force at all. Using the same equation of motion with , we can retrieve , the apex of the height. Which turns out to be very simple.

As you can see that it is just slightly above . As you already notice, is the final equilibrium position, which you can also get by using Newton’s First Law for the final condition only (net force from weight and buoyant force is zero).

We can now make an educated guess, since from the apex we have zero velocity but non-zero acceleration, after that point the balloon will undergoes dampening oscillation like before with almost linear drag force. This is because the speed is not significant enough. Then it will eventually stop at due to the missing energy of the system. So, we actually don’t have to deeply analyze the downward equation of motions :p.

Another one that’s interesting to me is if we substitute upwards , into the original equation of motion, so we got velocity as a function of height .

I am guessing that it will have at maximum of two zeroes. That means, there are only 2 possible values that caused . One of them is , of course, because the initial velocity must be zero. The other one is when it stops moving. I intuitively guess this, because needs to be positive, is linear, and the first terms will curve asymptotically to a constant value, so both will eventually intersects. The second solution of has to be approximately .

It would be good if someone can make a real experiment out of this or make some dynamic modelling to validate this.

Anyway, that’s all folks. Hope you enjoy the thought experiments.